At the turn of the century, a breakthrough invention was introduced in Silicon Valley. For Steve Jobs, it was the most innovative product since the personal computer. Jobs offered the inventor $63 million for 10% of the company. After taking one look at the product, Jeff Bezos immediately got involved and told the inventor “You have a product so revolutionary, you’ll have no problem selling it.” John Doerr, an early investor of Google and many other blue-chip startups, poured $80 million into the business without hesitation, predicting that this “would become more important than the internet.”

If these “superhumans” had full belief in this invention, it was guaranteed to succeed, right? Wrong.

That product was the Segway, the two-wheeled, self-balancing personal transporter. The inventor projected that within a year, sales of his newest product would reach 10,000 units a week. But six years later, they had sold only about 30,000 units in total.

Time called it one of the ten biggest technology flops of the decade. It was supposed to transform lives and cities, but today it is used only in niche markets. So, what happened? How were these extreme geniuses wrong about this? Why did their intuition fail them?

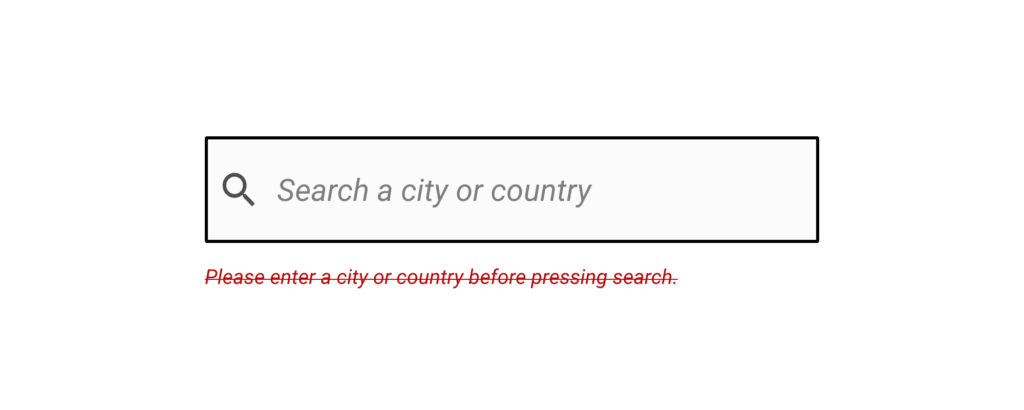

Our intuitions are only accurate in domains where we have a lot of experience. In dealing with unfamiliar ideas or products, you need to take a step back and assess them. Sounds familiar? As designers, we step back and research, benchmark, test, get feedback from users. If you don’t step back to analyze but always follow your intuition, you will fail eventually, no matter who you are.

“Designers resist the temptation to jump immediately to a solution to the stated problem… Instead of solving that problem, they stop to consider a wide range of potential solutions.” Don Norman

Thinking that this will be a breakthrough in transportation; Gates, Bezos and Doerr adapted this intuitive idea, but the project ended up as a massive failure. This doesn’t mean that every intuitive idea is bad; but, be aware that intuitions often fail in the wrong domains.

When is it safe to rely on intuitions?

You can trust your intuitions when (1) you’re in a predictable environment, (2) you have a vast amount of practice on a given field and (3) you can get immediate feedback on your judgment. If those conditions aren’t met, don’t trust your intuition, says Daniel Kahneman, author of Thinking Fast and Slow.

- Chess players certainly are in a predictable environment hence they lean on intuitions a lot.

- Tennis players practice for unimaginable hours within their life. Having no time to think, they use their intuition to hit the balls coming at them at 200 kmh; an exceptional ability.

- You have to receive immediate feedback on your thinking, to get out of the isolated thinking process and include other perspectives to your thinking.

“Unless those three conditions are satisfied, the mere fact that you have an idea and nothing else comes to mind and you feel a great deal of confidence — absolutely does not guarantee accuracy” he adds. If you have gained expertise in a specific domain and if you are a competent designer, your intuitions on that specific domain may be right as well. So, an intuitive idea can be original and successful in the right setup as Kahneman suggests.

However, the design process itself is not predictable and it is not safe to rely solely on our intuitions. That’s why we rely on users to understand their actual problems, test & iterate our designs. Besides testing and iterating our design, there is one more thing that we can do: to change our mindset from time to time while designing. We have to learn to think differently in order to look from other perspectives; which is possible with counter-intuitive thinking.

Counter-intuitive ideas

Let’s think about the coffee drinking experience before Starbucks was there. People enjoyed drinking coffees at home and saw this as a consumption rather than an experience.

Starbucks has transformed coffee consumption into an experience. Howard Schultz recognized that people looked for an escape from the day-to-day problems of life. That’s why going to Starbucks has become more than a coffee, but an experience of enjoying the environment.

A successful application of counter-intuitive thinking by Schultz. But how did he manage to come up with this counter-intuitive idea? As designers, how can we adapt counter-intuitive thinking?

Counter-intuitive thinking

Counter-intuitive ideas usually come from non-conformist people, Adam Grant says. Those who reject the default and explore whether a better option exists. It all starts with curiosity. They wonder why the default exists in the first place. Economist Joseph Schumpeter states that advocating for new systems often requires creative destruction of the old way of doing things.

If you look closely, you’ll see lots of correlations between counter-intuitive thinking and design thinking. Design thinking suggests to flip things, invert things, shake them up, to think outside of the box. It also suggests rejecting the default to explore new ways of doing things.

As designers, if we adopt the principles of design thinking, we will start swimming in the stream of creative and original ideas. Don’t forget that successful counter-intuitive ideas changed the accustomed systems throughout history.

Another successful counter-intuitive thinking example; Warby Parker

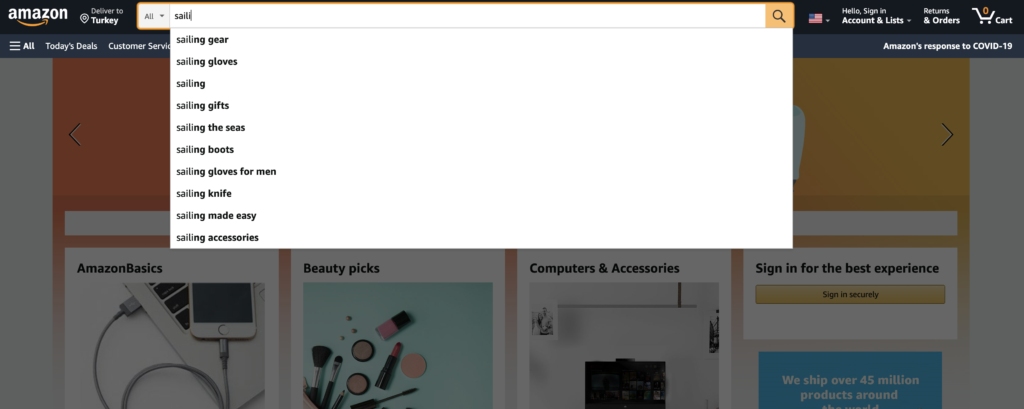

In 2008, Luxottica was nearly the monopoly of the eyewear market. Four friends wanted to get into the eyewear market and wanted to sell glasses online. During those times, no one was selling glasses online, and tackling this eyewear giant wouldn’t be easy. When they mentioned their idea to friends, they were blasted with a scorching criticism. Their friends didn’t believe that anyone would buy glasses online without trying them on.

Nevertheless, they launched the website in 2010 and called the company Warby Parker. What happened afterwards? GQ called them “the Netflix of eyewear”. They became the number one company in the list of the world’s most innovative companies in 2015; the three previous winners being Google, Nike, and Apple.

How did they break away from the conventional method?

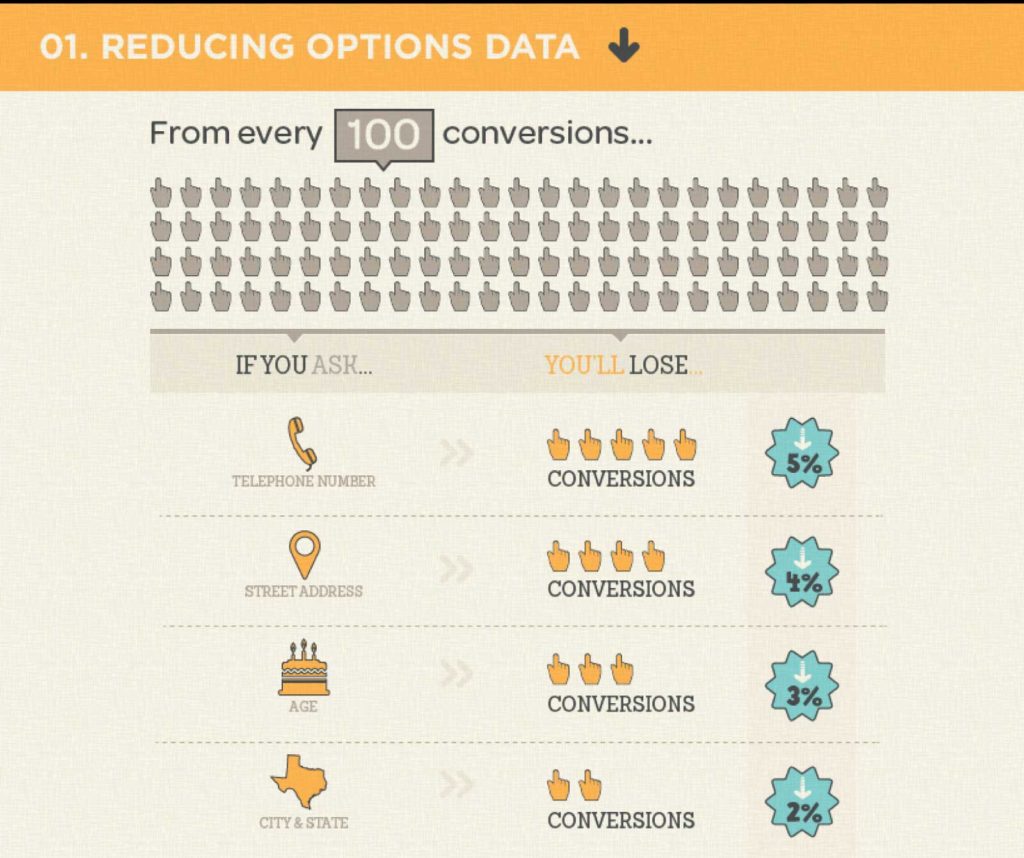

To make customers more comfortable with the unfamiliar concept of ordering eyewear over the internet they have come up with a free home try-on program, instead of free returns. The difference between the two is if a customer bought the frames with lenses and then returned them, Warby Parker would lose a lot of money, as the lenses were unique to the customer. But if customers tried on only the frames and returned them, the company could reuse them. Customers could order the frames alone without any financial commitment and simply send them back if they didn’t like the feel or look.

The free home try-on program was so popular that Warby Parker had to temporarily suspend the program within forty-eight hours of launch, to satisfy the over-the-top demands.

Evaluating original ideas

Research has been done with over two hundred people with the task of coming up with ideas. 87% of those ideas turned out to be completely unique. This shows that we don’t necessarily suffer from a shortage of original ideas, rather we have a hard time choosing the successful ones. The skill of recognizing successful original ideas is as important as coming up with them. Most of the original ideas die because of wrong evaluation.

It’s highly important to know that if we face uncertainty, our first instinct is often to reject novelty because of the risk it holds. Especially C-level executives tend to play safe and escape risks: they focus on the costs of investing in bad ideas rather than the benefits of piloting good ones. This leads them to kill great and original ideas. They tend to evaluate novel ideas by comparing the new notion to ideas that have succeeded in the past.

Therefore, we have to be careful while evaluating original ideas. We must not be fooled by our intuitions that tell us to see the risks firsts and search for previous successors. We have to get into our counter-intuitive mindset and look from other perspectives, research and test it to evaluate correctly.

Takeaway for designers

- Holding on to your intuitions may seem like a safe bet but intuitions often fail in the wrong domains. Similarly, the patterns you’ve detected in the past might not apply to the present.

- If you have come up with a fascinating idea, stop for a second. Note that not all of your original ideas speak to the users. Seek feedback, test your idea, do iterations.

- There is a hidden gem in counter-intuitive ideas and it is not easy to discover and handle it. To master this, one has to adopt the principles of design thinking. Furthermore, to chase counter-intuitive ideas, demolish the old way of doing things. Seek alternative solutions, ways to surpass the default.

- The skill of recognizing original ideas is as important as coming up with them.