“You are not the user!”, that is a phrase that most of us wanted to express at some point of one of the projects we participated in (hopefully, there is more than just one) or read about an influential article about the value of UX research, or in any UX-related subject. As UX professionals, we hope to begin any project with a discovery phase and incorporate quantitative or qualitative research to understand user needs, challenges and desires. Of course, all projects have limitations that may affect our timelines and budgets this way or another. These limitations not just apply to the beginning, but to the process of the project itself. Eventually, these constraints may affect our needs of inquiry in decision-making processes such as ideation and solution generation for building products with better user experiences. One of the best ways to mitigate effects and risks against understanding the real user experience is to approach UX research with a different angle, and strategically integrate it into the design process. Notably, discovery and ideation are the best stages in a project timeline. There are multiple methods and techniques to include user research, but for a kick-start, let me present you some ideas on how to acknowledge business goals, get onboard with stakeholders about the value of empathizing with users, investigate assumptions, and test user experience preventing conflict of interest among parties.

Begin with stakeholder interviews to identify business objectives

Stakeholder interviews allow you to ask about long and short-term goals, define the success criteria in terms of business, and boil down all these to UX vision and goals. Collecting insights about the business objectives enable you to empathize with different stakeholders and identify risks and opportunities. So, stakeholder interviews will ensure that your project has a clear start with a certain vision and predefined goals that every participant of the project has agreed on which will also assist you to incorporate key stakeholders into the design process.

Stakeholder interviews should be focused on the project scope. Therefore, you should carefully choose your key interview participants according to their influence on the success of your project. Those stakeholders having control over the budget of the project or sponsoring it in that organization are critical to talk to before giving a start to any project. At the end of the stakeholder interviews you should expect to understand capabilities and limitations of the organization, uncover critical roles, skills and experience and align all with business objectives.

Key stakeholders have limited time for a dedicated interview, so be prepared with your interview goals and questions designed especially to point out these objectives. Face-to-face interaction is the best way to communicate your purpose. Besides, you can observe your interviewee enriching the insights you collect even if due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions you have to run it remotely using an online communication tool such as Google Meet or Zoom. Each session should take no more than an hour and less than thirty minutes, ideally. To find the available slot, it would be better if these meetings are scheduled one or two weeks before the session. Since stakeholder interviews are designed to inform and align project participants with the main goals and facilitate focus on success, it is important to inform them about the results of in-depth analysis in a proper template either in a report or presentation.

Use triangulation method to demonstrate the value of empathizing with users

Qualitative research methods are best suited for inquiry of in-depth inquiry of user behaviors. Qualitative data offer a deeper understanding about the meaning behind user actions which leads us to user needs, challenges and desires. In addition, these kinds of research often require bigger budgets than e.g. surveys as in time and effort. Typically organizations that rely on quantitative findings in their decision-making processes have doubts about the validity of qualitative data. At that point “triangulation method” is just what you need.

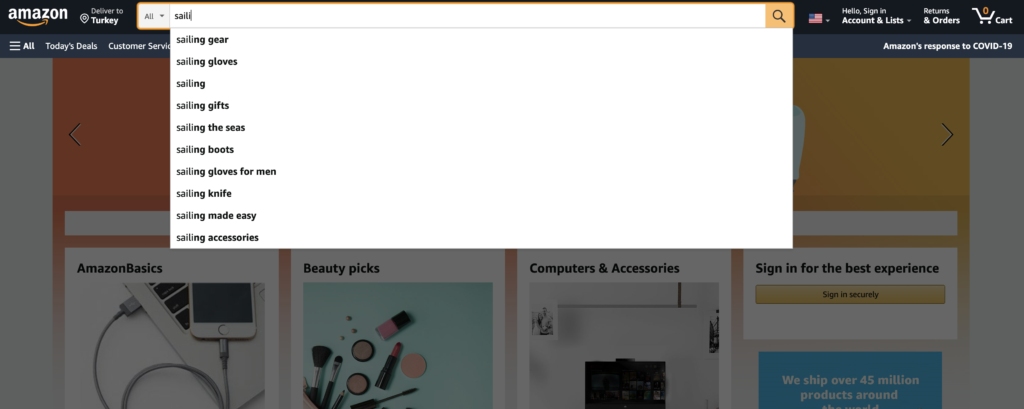

The thing with triangulation is that you look for specific qualitative insights that are consistent with the data you collected via quantitative methods or vice versa. For example, if you are using one-on-one interviews to understand the pain points users have on an online shopping website and discover some patterns, you can also design and launch a quick and short poll about the volume of users having similar pain points. Thereby, you can present your valuable qualitative data linking to the percentage of your potential audience. Even if it’s not the purpose of your research, it is sometimes the best way to communicate about the importance of your findings to dig further with follow-up research and to make your arguments stronger in terms of your quantitative-mindset colleagues or stakeholders.

Investigate assumptions to reconcile different opinions

To have proactive user research at the very beginning of a project is invaluable, however there is never enough time, budget or managerial support to initiate with proper research. What I mean by proper research is that developing a deep understanding about user needs to make design decisions easier, thereby hindering personal judgements and assumptions about what users want or have difficulties with. Making quick decisions based on assumptions – in the name of agile (yes, we all have been through this) – that are not validated with data would only seem to be doing it the right way. In fact, neither stakeholders nor designers are the real users and heuristics are not enough to lead design decisions at some point.

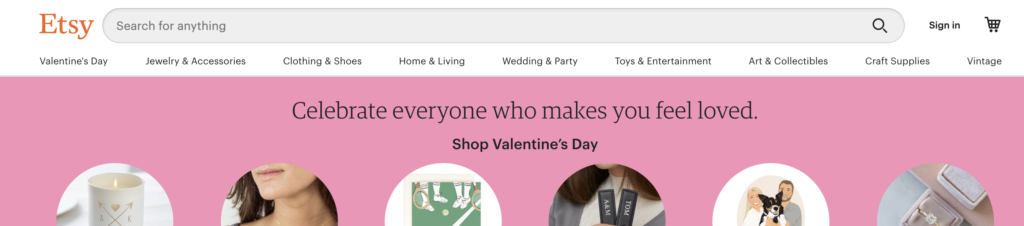

For creating ideal solutions for users, uncovering the problems that mostly affect the experience is the key. Therefore, you should bring your UX research skills onto the table to test the assumptions ahead. With proper UX research methods, you can test all the ideas generated in ideation and ground the most usable options to user data. Let me give you an example of a case. If you are a researcher in an e-commerce project about a category that users are not familiar with, you could offer a card sorting test to build an understanding of their mind maps and present your findings to your team and stakeholders to make better decisions about site navigation. Before taking such an initiative, you should be careful not to apply the wrong method, facilitating a biased study, or simply asking the wrong questions to the wrong people. Let’s say you should be precise about the basics of UX research design.

Test your design decisions eliminating conflict of interest between teams

Definition of done is a critical notion either in a feature release or a redesign project. If your team or just the development team is working agile, then the notion becomes more important and affects all of your research. That is because UX and agile have different understandings when it comes to definition of done. For agile delivering a working software means that the task is completed, whereas for UX testing the interaction with real users is a must before it actually means “working” whether with a working prototype or a manually crafted model. When we put time, budget and support issues that we have discussed above into the equation, as you can see these two definitions become conflicting.

Here is the tip to overcome this challenge; prioritize the most questionable patterns in the design decisions principally with your UX team and development team and test those patterns with users. Depending on your timeline and budget you can run usability tests moderated or unmoderated, focusing on your personas or just guerilla sampling. However, you should be able to rationalize your reasons to include or exclude personas in concern of the validity and reliability of your study. At the end of your research be prepared to deliver your findings to design and development teams with spotting areas of improvement.

The potential of UX research strategy

The potential of research methods is almost unlimited. You can either conduct one-on-one interviews or launch online surveys depending on your research questions responding to the needs of the project. Although there are some constraints such as time, budget, or support against UX research, the benefits strongly outweigh them. With all this in mind, you can show those benefits while strategically integrating research into the design process. You can use other techniques to align with stakeholders and business goals, denoting the value of user interviews as a data collection method and running quick tests for both investigating assumptions and preventing a conflict of interest among parties.