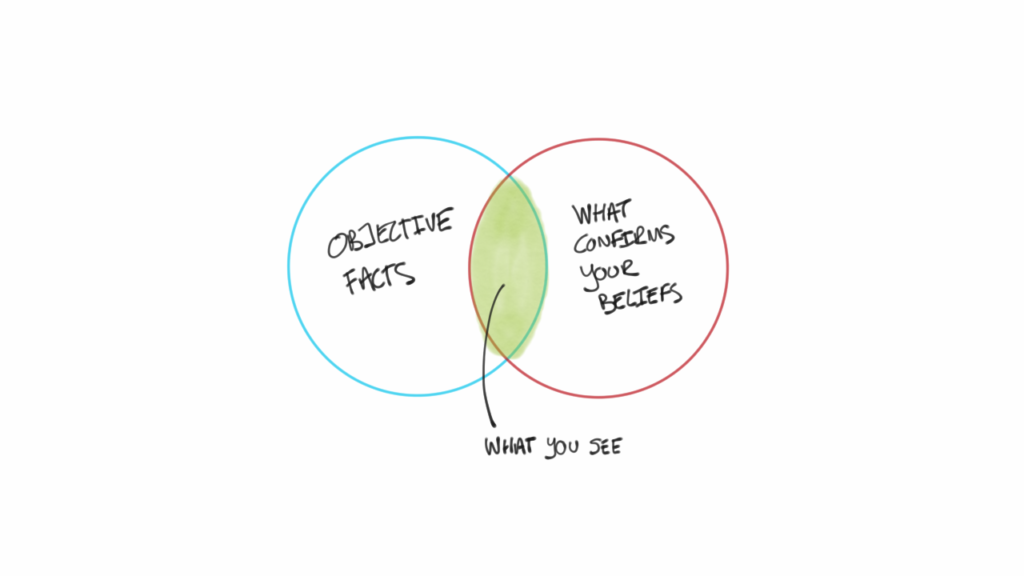

Although it is difficult for some to accept, humans are biased creatures; it is nearly impossible for humans to be %100 rational because they have emotions. As an average human, you probably want to believe that your convictions and knowledge are the result of years of experience and objective analysis. The truth is that we are all under the influence of an insidious problem known as “confirmation bias.” We would like to think that our convictions are rational, logical and objective, but our convictions are in fact the result of us giving our attention to ideas that support them.

What is confirmation bias?

Confirmation bias (confirmation prejudice) is a tendency to seek out information that confirms one’s own desires, ideas, and convictions; and to ignore counter opinions, while investigating a subject, evaluating a situation, making decisions, or even remembering an event that happened in the past. Even if we take into account that every idea has positive and negative features, our mind unconsciously seeks information that confirms our belief. With this information, we want to defend and provide justification for the ideas that we believe in. It is often difficult to accept a different idea on the same subject. This is because we are prejudiced against change and do not easily want to change.

David McRaney explains how confirmation bias affects our awareness and the way we perceive our environment. When you think of buying a particular brand and model car, you suddenly start to see many similar cars in traffic. After a long-term relationship, every song you hear sounds like a love song. When you have a baby, you begin seeing babies everywhere. Confirmation bias sees the world through a filter that is shaped by your interests, wishes, and feelings, McRaney says.

This filter can momentarily change depending on your interest and mood, and confirmation bias – as it tends to support our changing convictions – also affects how we process existing neutral information.

What is an example of confirmation bias?

For example, when your relationship is happy, you do not see any mistakes in your partner and even ignore your partner’s negative personality traits. You perceive everything as perfect. Contrarily, when your relationship starts to go poorly, or when you are in a bad mood, all the mistakes and negative personality traits of your partner which you didn’t mind before begin to bother you. You are still with the same person, but the way you perceive what they do depends on how you feel.

How does confirmation bias affect our thinking?

Confirmation bias also affects your memory. You can interpret memories and events according to your own ideas and even alter them in extreme situations. A well-known, classic experiment conducted by Hastorf and Cantril explains this situation quite well. Princeton and Dartmouth students watched a football match between their two schools. At the end of the match, Princeton students remembered that the Dartmouth team made more fouls and Dartmouth students remembered that the Princeton team made more fouls. The two groups of students, both fanatically believed that their teams played better. The selective perception and memory of these two groups led them to construct different realities even though they were watching the same event. People who are members of a group usually obtain the perspective and filter of that group, and this frame and filter distort the way each group member perceive their environment. In the same way, people with prejudice tend not to recall the characteristics of stereotyped individuals outside of those stereotypes. People therefore take less notice of information that conflicts with their expectations. When we think of the same example, the students who watched the match did not consider or remember the good plays of the rival school’s team.

When it comes to personal passions and interests, confirmation bias – which is effective in moments of evaluation, judgment, and decision-making – can become more violent when confronted by an opposing view, as it exists because of an over-reliance on one’s own beliefs, potentially leading to dire consequences. This phenomenon is frequently seen in the management and recruitment of positions of companies, in medicine and in politics. Especially in this realm, people do not think they have particular prejudices. Because most of the things that occur in the brain are not accessible to the brain itself, people are not capable of understanding the times when they are biased. While individuals realize that others act in deceptive and biased ways toward themselves, they forget that they, too, are human.

A Princeton University research team offered an extensive list of prejudices to a group of people and requested them to list the number of prejudices they possessed and the number the average person possessed. A majority of the test participants claimed that they were less biased than the average person. According to a similar study conducted in 2001, doctors think 84 percent of their colleagues will be affected by gifts coming from pharmaceutical companies when diagnosing and treating patients. But only 16 percent thought they would be affected in a similar way.

Individuals tend to overestimate or underestimate the impact of certain situations and decisions on themselves and other people. Therefore, in cases in which judging and decision-making duties are endowed on one particular person or in cases of external intervention into objective assessment, the decision-maker is often deceived by his or her prejudices and ends up making decisions that negatively affect those impacted by those decisions. On the other hand, people may also tend to exaggerate or underestimate the effects of their decisions. As a result, the decision-makers are more biased than they think, but we can safely say they are less biased than others suspect about them.

Wason’s work aims to show that even when new information is presented, people stick to their first instinct and do not take an approach that tests a hypothesis optimally. You can review a sample of this test in the video above. In this experiment, people were given a set of numbers with a rule. Participants were expected to first mention another set of numbers that conform to this rule, and then tell the rule set for this series. The person conducting the test explained whether the number indicated corresponded to the rule and whether the rule was correct or not. The number series for the test was indicated as 2, 4, 6. Many people suggested the series 6, 8, 10, or 8, 10, 12, and guessed that the rule was consecutive pairs. The series conformed to the rule, but the rule was not consecutive even numbers. The participants developed quick judgments about the patterns they had seen and established a quick hypothesis. However, despite the fact that the rule was pronounced false, they continued presenting other series that confirmed their hypothesis instead of rejecting the hypothesis. Few participants tried presenting a series of numbers that could reject their own hypothesis. This experiment shows why the scientific method is so critical. When a theory is created on a particular subject, we should try disproving that theory because only when the theory can no longer be disproven can we achieve genuine knowledge.

It is important to approach life with curiosity rather than judgment to prevent this bias. Whenever you try to prove that you are right in every argument, you are deceived by confirmation bias. Even worse, since you’re constantly trying to be right, it’s inevitable you have to avoid risky problems and are likely to pass responsibilities to someone else to focus on simpler things out of your fear of making mistakes. In this case, your life experience will be limited. If you approach the problem without fear of making mistakes and establish a proper relationship between the past and the future, you will achieve the right definition and open yourself to new insights. Trying to understand others’ alternative views and perspectives instead of insisting on your own ideas about what you are presenting or working on will help you to correct and reform your perspective on the subject. In fact, getting together with people who have different opinions, introduce you to different methods, make efficient contributions and, in some cases, play devil’s advocate is very helpful for escaping the confirmation bias. In other words, when you have an idea, try to disprove the idea and discover the features that remain out of the pattern in your mind. Only then will you reach the best objective without deceiving yourself and acquire more comprehensive information on the subject of your curiosity.

In terms of the broader society, those who have the authority of decision-making – such as doctors, judges and administrators – seek to acquire more genuine information than others think they do, but they overlook more things than they themselves acknowledge. Since the brain can’t see its self-deceit, the most effective way to avoid prejudice is to avoid the situations that cause it, and to minimize external influences that make the objective assessment difficult. For example, confirmation bias may be prevented if doctors do not accept gifts from pharmaceutical companies and if judges do not handle their relatives’ cases.

References and suggestions for further reading:

- Wason Rule Discovery Test

- Daniel Gilbert – I’m O.K., You’re Biased

- Daniel Kahneman – Thinking, Fast and Slow

- Bill Pratt – What is Confirmation Bias

- Buster Benson – Cognitive Bias Cheat Sheet

- Lakshmi Mani – Confirmation bias: Why you make terrible life choices

- Catherine A. Sanderson – Social Psychology